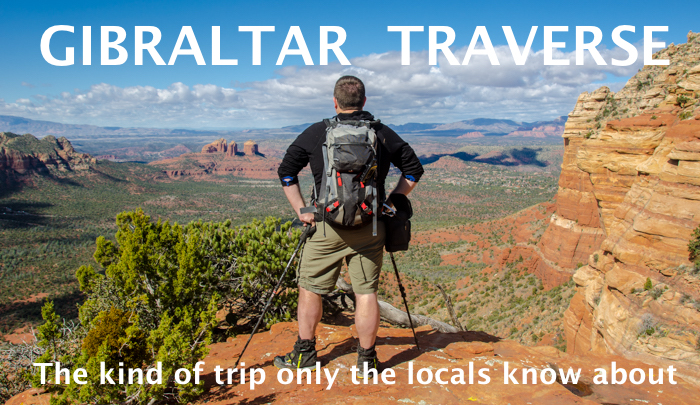

As our Arizona trip was drawing to a close I had one more adventure lined up. One of my Thursday-night hiking buddies had moved to Sedona and had put together a hike that was just on the right side of crazy. It would be just what I needed to help me really experience the area.

Since I had to drive from Phoenix we didn't start too early. The sun was just breaking over some of the famous red rocks as we followed the trail through the scrub and into the Munds Mountain Wilderness. From the very beginning it was jaw dropping. Heck, it's draw dropping from the parking lot! When you're standing below a massive rock wall carved my thousands of years of wind and rain it's beyond jaw dropping. Steve, the Northwest transplant, collected me and we entered the woods along with temporary Sedona resident, Ed.

The plan was to follow the trail into the wilderness until it petered out. Then we'd follow the dry creek to its end and climb up to the top of the plateau. From there, we'd work our way back along the ridge, over two lesser summits, to the top of a rock Steve called, "Gibraltar." A quick descent and we'd be back where we started. All told it'd be under eight miles and 2,000 feet of gain. Back home we'd knock that out in a few hours. No problem.

Well... Not quite no problem.

The trail into the wilderness was great. We were in the trees for a while, stunted, spindly trees that felt alien, and then emerged onto slickrock. The trail disappeared, but we were able to follow the cairns... er... "ducks," as the locals call them. (Why "ducks?" Apparently sometimes they have a stone near the top that points the way and makes the pile look like a duck.) When the ducks ran out we dropped into the dry creek bed.

It's clear there is water in the creek from time to time, mostly because it's piled up debris in some spots. The debris ranged from piles of leaves (easy) to impenetrable tangles of branches and cactus and rattlesnakes. (Technically there were no rattlesnakes, but there might as well have been.) The creek, now with a trace of water, turned back toward the cliffs and dead ended at the base of a waterfall.

I know! A waterfall in the desert! It was almost as crazy as the last time we saw a waterfall in the desert, except this time there were no crowds of tourists pushing strollers. (Seriously, last time it was a little crazy.) We had this all to ourselves.

Don't get too excited, though, this was more a wet spot on the wall with a little pool than the type of waterfall I'm used to at home. Still... WATER! But we weren't there to find water. Although we stood at the base of a solid wall of rock Steve assured me the route went. Up a bit. Right a bit. Up some more. Don't grab that plant for a veggie belay or you'll pay for it. And don't, definitely don't look down.

Atop the ridge the views were expansive. Big blue sky and glowing orange rock everywhere. We crossed the ridge to the southwest to stand on the "Diving Board." The Diving Board is a finger of rock that extends from the ridge in an only slightly terrifying way. It doesn't feel like it's going to collapse, but it's certainly an airy place to stand.

The view made up for it, though. The famous landmarks in the valley were set against the blue sky. We were about 1,000 feet above the valley floor and it was straight down. Not kind of down, but straight down. Even a little overhanging in places. Some of us were wise and stayed well back from the edge. Others bellied right up to the drop. The truly foolish did some freaky yoga pose that made my stomach tie itself in knots.

I'd have been completely happy to be done at this point. The challenge of navigating the dry creek bed and climbing to the ridge had been amply rewarded with views unbelievable to someone from Washington. We were only half way done, though.

From the Diving Board we made our way across rock slabs and dodged low-lying, sneaky cactus. Steve was wise and wore pants. I was in shorts and low gaiters. Ed was wearing sandals. There was a bit of blood donation on the way to the first summit.

We paused and had lunch as the clouds started rolling in. I looked ahead and thought, "There's no way this is going to go." No trail and a steep, steep descent to the next saddle. But Steve assured us it would be good so we pushed on.

This kind of off-trail adventure isn't common in the Northwest except during winter when the snow allows for travel over the brush. After a week of hiking in the Southwest I had finally stopped seeing every bare spot as a fragment of trail and instead saw it as what it was: A momentary respite from the attack of pointy plants. (I thought I'd seen all the pointy plants, but there were some new, vicious plants. The flora here is just wonderful.)

At the bottom of the saddle (Steve was right!) we crossed the head of an open gully and started up the next hill. Going up was easier than going down. That always seems to be the case when on sketchy terrain. We traced our way up the easiest line to the second summit.

Back down, back up. We actually saw some people on the third summit, which Steve referred to as "Gibraltar," but they were long gone by the time we got there. Looking back the way we had come it didn't look like an easy traverse. The thick brush was broken up by cliff bands and memories of a million thorns eager to scratch left me surprised we had actually made it to the final summit.

With no more up it felt easier than ever to descend. A broad ramp took us down the face we'd seen from the beginning of the hike, but the broad ramp became less and less broad. Instead of a light-hearted walk I found myself concentrating on foot placement. And then we got to the spot Steve referred to as, "Sporty."

There are lots of ways to talk about a particularly challenging section. You might grade it with the Yosemite Decimal System or describe it as the "crux." If it's lousy I call it, "sketchy," but in Sedona that one spot is called, "sporty."

The "sporty" section was a 15 foot drop with only a two foot ledge below it. Slip off the ledge and you're tumbling down the steep slope for at least a few hundred feet. All day I'd been leading us up and down, but when I tried to figure this out I backed off and let Steve go first. It took him just a few moments to find the hand and foot holds to get down. He helped Ed find those same holds to get down.

Great. My turn. I started down and couldn't make it work. I went back up. I went into it again and had to pause while I frantically felt for the hold with my foot, but I couldn't find it. I only got down because Ed guided my foot to the right spot and I was able to transition to a manageable position.

Steve said it was easy for him because he'd been up and down this way previously. I'm not sure that's the only reason, but I'll accept that his local knowledge gave him an advantage.

The trail switchbacked down the side of the mountain before depositing us at a saddle between Gibraltar and a spectacular, but unnamed rock formation. A bit of trail led higher on that rock, but our day was about done. My legs were still shaking from the adrenaline rush of the sporty section so I didn't argue as we continued out the trail and back to the cars.

It goes without saying that this kind of trip is pretty much impossible without someone that knows at least the kind of terrain you're in if not the actual route you're attempting. Without Steve I probably wouldn't have gone much further than the waterfall or the diving board. I certainly wouldn't have traversed the entire ridge and made it down the face of Gibraltar.

It's that local knowledge that is so valuable. When you can you should take advantage of it. When you have it, share it.

And maybe bring a rope next time.